Our Founding Friars

✝ FR. BENEDICT JOSEPH GROESCHEL, CFR

Jersey City, NJ

Professed: September 1, 1952

Finally Professed: September 1, 1955

Ordained: June 20, 1959

Died: October 3, 2014

✝ FR. ANDREW JOSEPH APOSTOLI, CFR

Bronx, NY

Professed: August 7, 1960

Finally Professed: August 11, 1963

Ordained: March 16, 1967

Died: December 13, 2017

✝ FR. ROBERT STANION, CFR

Somerville, MA

Professed: March 20, 1967

Finally Professed: May 8, 1972

Ordained: May 16, 1992

Died: March 23, 2009

FR. GLENN SUDANO, CFR

Brooklyn, NY

Professed, August 16, 1979

Finally Professed: September 16, 1982

Ordained: June 2, 1984

FR. STAN FORTUNA, CFR

Yonkers, NY

Professed: March 16, 1981

Finally Professed: August 16, 1986

Ordained: December 8, 1990

Bishop BOB LOMBARDO, CFR

Stamford, CT

Professed: March 16, 1981

Finally Professed: August 16, 1986

Ordained: May 12, 1990

Pope Francis appointed Bishop Lombardo as titular bishop of Munatiana and auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Chicago on September 11, 2020. On November 13, 2020, he was consecrated by Cardinal Blase Cupich at Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago.

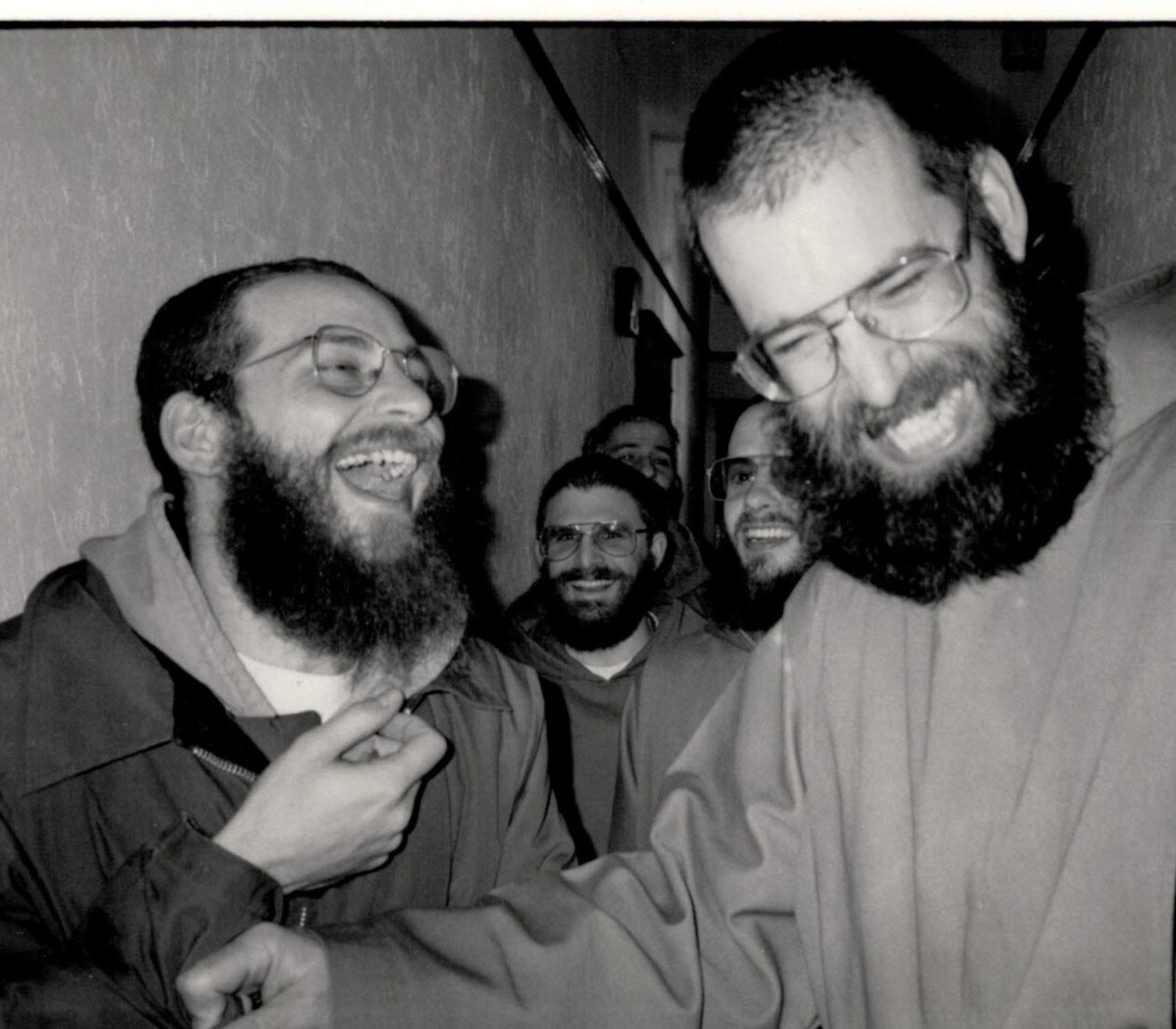

Introduction

The Community of Franciscan Friars of the Renewal was begun in 1987 by eight Capuchin friars desiring to work more definitively for personal and communal reform within the Catholic Church. The life and apostolate of the friars are rooted in the ideals and spirit of the Capuchin reform born in the early 16th century.

When standing beside some ancient monastic orders, such as the Benedictines or Carthusians, we Gray Friars are rather insignificant. When compared to the robust apostolic and influential religious societies, such as the Jesuits or Salesians, we are very weak and spindly indeed. Church historians might well be quick to point out that the ink is still moist on the first page of our chronicle; while others in time-tested communities might wonder whether we are actually seaworthy. These latter may strike a let’s- see posture, watching from a distance to see whether we survive the high seas, being only at the start of a voyage.

Renewal

By the grace of God, the Franciscan Friars of the Renewal came to birth twenty five years ago, in the spring of 1987, which was, providentially for us, a Marian year. That year, eight finally professed Franciscans (I being one of them) began a renewal at a time in history and with a vision that were quite similar to those of our Capuchin confreres in sixteenth-century Italy. We have much to say about—and, indeed, a debt of gratitude to offer—Pope John Paul II, who was a source of instruction and inspiration to us. If we survive the storms to come, one reason will be the strength of his Christian witness and the ballast of his wisdom and devotion.

History attests that, in every age, attempts to bring renewed vigor and focus to religious life have met with a predictable amount of fear and distrust. Times of reform are often dramatic and accompanied by the clashing of opposing ideas and expectations. The opening chapters of both the Capuchin and Carmelite reforms were not lacking in strong characters who wrestled with serpentine subplots. Understandably, to examine every aspect of our own early days would be an indiscretion. Despite the human backdrop, we should not become distracted but center our attention on the drama unfolding on center stage. No doubt, one can be both surprised and inspired, and at times perhaps entertained, by the mysterious interplay between divine grace and human weakness. Any authentic attempt to bring reform and renewal to an institution is accompanied by pain. Timid attempts to make life better rarely bring effective results. Planes never lift off the ground at low speeds, regardless of the sincere intentions of pilot or passengers. In another metaphor: tepid water makes weak tea.

Unlike us and our Capuchin forefathers, many religious communities enter the world quietly and unannounced, like spring crocuses. It often happens that a prophetic or charismatic founder or foundress sees a need in the Church or the world and personally responds to that need. Soon, others follow, and a community is formed. With us it was different. We can point to no founder, although spiritual leadership was far from lacking. Unlike many communities, we were not slowly and meticulously built, but rather quietly conceived and painfully born. Like human life, some religious communities often come into existence only by expending considerable blood, sweat, and tears. Communities of reform are indeed breech babies, who bring pain to the mother during their birth. To the uninitiated, the entire event resembles an unfortunate amputation; yet in reality it is the fortunate arrival of new life.

The Grayfriars

The Franciscan Order, begun eight centuries ago, can best be compared to an old tree: it has deep roots and diverse branches. Its history accounts for the various types of Franciscans, who have emerged over the years, each identified by a different cut and color. One of the tree’s larger branches came into existence in the early sixteenth century, an era ripe for change. Members of the Franciscan reform movement, which emphasized evident material poverty, contemplative prayer, evangelical preaching, and care of the very poor, became known as the Capuchins, a nickname given by the people because of the friars’ long, pointed capuche, or hood. It is from this noble and holy branch that we owe our identity and existence. In a symbolic return to the early Franciscans who wore poor, undyed wool, we changed the color of our habit from the familiar coffee-colored habit of the cappuccino to the original gray. To this day, Franciscans in England are known as Grayfriars.

When I first entered Franciscan life more than twenty-five years ago, I was like many novices: idealistic but perhaps somewhat unrealistic in my hopes for a more authentic and vibrant expression of our life. Being young, I had high ideals and a hunger for something more, something greater. Unfortunately, spiritual immaturity often draws our attention to heroic and dramatic things, such as radical poverty, and less to more important things, such as humility and charity. Now that I am older, I too smile inwardly at the innocent naïveté of the postulant who wonders why the friars don’t go barefoot through the city streets and beg their food door to door. Yet at the core of it all there rests something good—in fact, something quite beautiful. Surely, when we hold within ourselves some high ideal or great dream we may find ourselves alone, feeling odd and isolated, even from family. I remember describing myself to my spiritual director as being like a sailor standing on the deck of a large ship and pointing excitedly toward an enticing island on the horizon. The older, more seasoned sailors remained unmoved or even laughed, saying that the island was either abandoned or impossible to reach. Some said it was not real, but a mirage. Thankfully, I was not alone in what I was seeing and deeply desiring, though from a great distance. By myself I would not have found the strength to leave a secure ocean liner for a flimsy eight- man lifeboat. As I look back, it is not surprising that so few of our confreres openly praised our courage, while some quietly questioned our mental health.

Capuchins in the City

By God’s design and the assistance of friends like John Cardinal O’Connor, archbishop of New York, and saints like Mother Teresa, we found ourselves safely on the shores of the South Bronx. As some say, we hit the road running, because we immediately rolled up our sleeves and began to work. We weren’t aware of the many obstacles ahead of us, but, thanks be to God, youthful ignorance and enthusiasm are helpful in surmounting big hurdles. Almost every day we had to deal with new situations and unanswered questions as we made our humble outpost a home in an almost abandoned and drug-infested neighborhood.

Most days were spent scraping, stripping, pulling up, and tearing up—we call it Capuchinizing—getting rid of the old, ugly, unnecessary things such as paneling, rugs, and wallpaper. The rectory parlor became our chapel almost as soon as the tabernacle replaced the television. All the old air-conditioning units were put curbside, to the delight of local drug addicts. Somehow, in the midst of our manual labor, we found the time for so much more. Most important, we prayed, although during the summer months we were serenaded outside our chapel windows by police sirens and ungodly “music.” In the midst of this we managed to serve the homeless, counsel drug addicts, and teach the children who found their way to our door. No doubt it was God who not only gave us the vision to see our Shangri-la in the distance but also brought us there safe and sound, as if carried in the palm of His hand.

From day one, our desire was not to create a new form of religious life or observance but rather to set ourselves securely upon our own ancient foundations. For this very reason, none of the original eight Friars of the Renewal see themselves as founders. We do not see ourselves as prophetic architects but rather as simple builders. In this regard, renewal does not mean some new spin on Franciscan life, nor is it an innovative amalgam of religious traditions. Rather it means a return—not simply going back, but something deeper—a return to roots. We were and still remain completely uninterested in programs and trendy ideas that promise spiritual renewal. Real renewal means daily conversion, and this is a long, painful road. The holy Gospels are our map, the saints are our guides, and the sacraments are our strength for the journey.

Our community began in 1987 with eight friars; today we number more than one hundred and forty. While, certainly, steady growth and expansion are impressive, they are not everything. The strength of a tree is not measured only by the width of its trunk or length of its limbs but also by its roots. The quality of vocations is more important than quantity, yet both are related. Both depend on the soil in which they are set. Religious life will not only survive but will flourish when it is firmly planted in the heart of Christ, who is the heart of the Church. This means nothing less than: a clear identity, total fidelity, ardent devotion, daily prayer, and sacrificial service, especially to the poor. This is what young people are seeking. This is the secret for any community intent on authentic renewal. Young eyes need to see something bright and beautiful. How sad when their longings and excitement are met with indifference and unbelief.

As an artist steps back a bit to see how his work is taking shape, so too this book has personally provided for me a needed distance, a certain space, to see a wonderful divine work still in progress. Like poor peasants who live in the foothills of the Alps, all of us can become oblivious to something grand and majestic in our own backyard. Would that each of us might have such a book as this one to help us take a few steps back—to see what God is quietly accomplishing in our lives. May He be praised. -Fr. Glenn Sudano, CFR